"Well, we've certainly brought light into these people's lives!"

"Well, we've certainly brought light into these people's lives!"

"Well, we've certainly brought light into these people's lives!"

"Well, we've certainly brought light into these people's lives!"

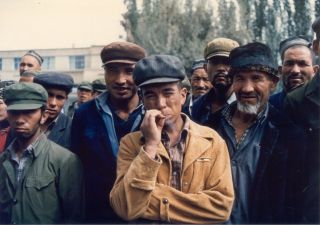

My two companions laughed (a little nervously) in response to this remark and then turned their attention back to the swelling horde of fifty or more Uighurs, Kazakhs, Kirghiz and others who were drinking us in with an almost rapturous intensity. As big-nosed, hairy foreigners (few Asians have beards you can see), we were used to being stared at, but never so copiously, nor so unjustly, as here in Aksu (or was it Korla) in far west China. We felt it was unjust because the natives were so picturesque themselves: the wayward teeth, the funny hats, the various physiognomies and complexions--some even had blue eyes. A few of the elders among them had decided we were Russians, neighbors from the North:

"Andrei! Andrei!" they cried.

"Andy, John, and Erich!" we cried back, "and we're from the United States."

After a puzzled pause, there were a few more shouts of "Andrei" and then many started stretching their hands into the air to indicate with marvel our great height.

"We're Americans," repeated John, the Californian, "and we're so tall because we eat mega-vitamins!"

Eventually the mob started pushing too close, and we took refuge on top of our bus.

"You'd think they would have heard of America," said Andy, a sometime student at Dartmouth, "I mean, I see Michael Jackson and Brooke Shields all over the magazines."

"Let's sing them a song," I suggested. And so, feeling like rock stars above all the upturned faces, we sang:

God Bless

America

Land of our

Home

Stand beside

us

And guide

us

Rumty-tum,

tumty-tum, tumty-tum.

It was just by whim that we had come so far west in China. In Japan, where I had settled for a while, I had found a large-scale map of Tibet, and had been ravished by the sight of hundreds of lakes, all in apparently uninhabited country, and all at altitudes beyond anything available in Japan, or most anywhere, for that matter. I planned to go through south China to Tibet, and then to Nepal, as quickly as possible. If it was possible at all, that is. The Chinese embassy in Tokyo had denied that anyone could cross the Nepalese-Tibet border. But I knew from experience that Chinese bureaucrats love to deny things. At the Chunking Mansions, the cheapest and sleaziest place to stay in Hong Kong, I learned more. There, notices on a crowded bulletin board, besides naming local stores that sold cameras with no insides, affirmed that it was possible to exit China to the South. One just needed the permits.

To my surprise, I got one. I traveled from Hong Kong to Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan province. And there, from elated travellers hurrying out of the public security office, I learned that permits were being issued that very day. The rumor was that the Chinese in Tibet had been celebrating the 35th anniversary of their rule of that region.

Foreigners had been excluded from finding out whether the Tibetans were celebrating too. With the displays over and access permitted, it was now a matter of getting there.

Rich, lazy people could fly. That was out. There is a road to Lhasa from Chengdu. That, it seemed, was out too--washed out. In a road crossing three great rivers (the Yangtse, Mekong, and Irrawaddy), such news came as no surprise. A few people tried hitchhiking west anyway, but were caught and turned back by the police.

The only approved overland route was by train North to Lanzhou, then west to Golmud, then by bus south to Lhasa, on a paved road. John the Californian and I happened to be on the same train out of Chengdu.

In a Lanzhou restaurant, trying to order braised camel's feet, John and I discussed our plans.

"If we fork southwest to Golmud now," I said, "we miss out on the silk road: the Gobi desert, the great wall, and the huge Taklamakan desert which Sir Aurel Stein explored. He said that the Sahara was practically a rain forest compared to the Taklamakan, and then complained when his men wouldn't explore further on a diet of only dirty ice chips."

"That all sounds fine to me, except for the dirty ice chips," said John. "I'm not in any hurry."

"How long have you been traveling anyway?"

"Well, I had a computer job back in the States, and was earning plenty of money. It was what you would call a challenging job, even. But wow, so what, really. I mean, was I just going to run around attending meetings, making this decision or that decision for the rest of my life? So I decided to go see India and places. I bought a ticket to Thailand--have you been to Thailand? My God, what a place. A round trip ticket, for a year. That was almost exactly two years ago, and I don't feel any urge to quit yet."

"Neither do I, so let's hit the silk road. After all," I asked, pouring beer into our tea bowls, "when will we pass this way again?"

"On our way back to Golmud, most likely. You haven't said how we're going to get back, or get to Tibet. What's in that dish over there?"

"Meat. Also, teeth."

"Ew, like, gag me with a chopstick."

So our next stop was at Jiayuguan, western

terminus of the great wall, here reduced to a

wall of mud about two meters high and one across. More impressive

was the fort, whose gate opened to the barbarian

lands beyond. To my gratification, as I gazed

west, I saw some distant yurts, and what appeared to be a picturesque barbarian rodeo.

So our next stop was at Jiayuguan, western

terminus of the great wall, here reduced to a

wall of mud about two meters high and one across. More impressive

was the fort, whose gate opened to the barbarian

lands beyond. To my gratification, as I gazed

west, I saw some distant yurts, and what appeared to be a picturesque barbarian rodeo.

The desert between us was cut by hidden gullies, so when I saw the yurts again, they were quite close. I took one look and scrabbled madly at my camera knobs. Here were monks telling prayer beads, horsemen in single combat. And over there were the Chinese movie cameras. I pointed mutely at them when John came up a while later. We singled out a watermelon-eating actor, who looked like a Star Trek villain, and asked him about the movie. Our poor Chinese prevented us from learning anything more than that it was a historical drama, and that the men in the square tents were fighting the men in the round ones. We shared some watermelon and then went back to the fort.

The bus back to town was mobbed; Chinese were climbing in the windows.

John elbowed his way inside, but I felt put off, so when nobody was looking, I climbed on top and lay low. To my surprise, the bus started off and there was no outcry. Below me I could hear John call out:

"Erich, are you on the bus?"

"Yes!"

I laughed and rapped on the roof. Then I lay staring at the passing clouds and treetops.

Continuing west on our way to Turfan, we entered Xinjiang Province.

This part of inner Asia has a long, varied history. China has had an interest in it at least since the first century bc, when the Han dynasty made efforts to control the silk road. Huns, Mongols, and the USSR have made similar efforts to rule. A period of Soviet influence waned during World War II, and despite local uprisings, revolution in China, and renewed Soviet attention, this land became the Xinjiang Uighur Semi-autonomous region of China in 1955. The major cities as one travels west along the northern rim of the desert are Turfan, Urumqi, and Kashgar. Turfan summoned up grade-school memories for me of beautiful oases; Urumqi was reputed to have turned very Chinese, and we judged it worth missing; Kashgar, as far west as one could get in China and not be in Pakistan, was only recently opened to foreigners, and began to frequent our thoughts. But it was still about a thousand miles away.

Uighurs are the major ethnic group of Xinjiang, and their language is not related to Chinese at all, but to Turkish, so that John and I did not even recognize the first Uighurs we met.

There were two pretty girls on the train, whom we supposed to be Italian. We spoke invitingly in English. They responded in Uighur, which sounded nothing like Italian. Less hopefully, we spoke in French. The women replied in what we took to be pig latin. Thinking more sanely, we realized it was Esperanto. They had to be Chinese, we immediately knew. Sure enough, conversation proved possible in Mandarin. The women were engineering students on their way home for vacation, apparently very at ease in Chinese bureaucracy, for they wheedled sleeper berths from the conductor, and departed smiling, long before we managed the same feat.

Turfan

proved worthy of our diversion. As we had already seen, there were

pretty girls in abundance, but there were also

colorful dances, a cool grape arbor at the

hotel, a good black market rate, droning music in the bazaar, melons, mutton, flat bread and bagels.

Turfan

proved worthy of our diversion. As we had already seen, there were

pretty girls in abundance, but there were also

colorful dances, a cool grape arbor at the

hotel, a good black market rate, droning music in the bazaar, melons, mutton, flat bread and bagels.

So it was with the complacency of the well-fed that we and our newly-made friend Andy, stood in the dismal town of Daheyon and waited for the train. Andy was a good-natured, if dangerous-looking American of Ukranian origin who had a keen entrepreneurial imagination. He surprised us several days later by admitting he was a student at Dartmouth, had been studying in Beijing, and was still only nineteen.

"So are we going back to Lanzhou, or on to Kashgar?" asked John.

"I'll do what you guys do," Andy replied.

"I'll do what Erich does."

It was the common where-shall-we-eat dilemma. So I said:

"We could go back, see the famous caves of Dunhuang, and proceed tamely on to Golmud and Lhasa. Or, we could undertake a grueling four-day desert drive, go further in the wrong direction, and probably catch hepatitis. I think I know what Indiana Jones would do."

"Kashgar! Kashgar!"

Grueling described that bus ride very well. Sometimes fear interrupted the dusty, rattling tedium, when we saw yet another overturned car or exploded horse, but otherwise there was nothing to do but sit, squint, and hope for an oasis, where we could look forward to being stared at by the locals. It was a measure of my boredom that I started remembering geometry problems and posing them to my companions. And it was a measure of theirs, I think, and the long hours, that after a few rude suggestions they eventually solved them.

In my exuberance at arriving at Kashgar, or at least getting out of the malodorous bus forever, I broke two panes of glass by squirming out of the window. The twenty dollar fine neatly doubled my ticket price, but there was plenty to take my mind off it in the city itself. The first order of business was finding a hotel. We found a flat horse-cart, loaded our packs, and sat down on the edges. The driver took us down a long avenue lined with dusty trees. On one side there was a blue lake, over which I observed a seagull flying. I was surprised to see one, since I had read that Kashgar was the city farthest from any ocean.

Our hotel was a modern, Han Chinese affair, all functional concrete painted pastel colors or inlaid with dull stones. Organized tour groups frequented this hotel, which meant among other things that only Foreign Exchange Certificates--FEC or `tourist money'--were accepted. Budget minded travelers in China try to use Renminbi or `peoples' money.'

Nominally the two types are equal, but in practice 1 FEC equals 1.6 Renminbi or more. Changing money thus affords a fat profit (when first in Canton I exchanged out of pure greed, without even knowing exactly what was going on). But it needs guile to use peoples' money, since foreigners (except students) are not supposed to have any. Remote places are usually easy: the inhabitants do not even recognize the crisp FEC notes.

So after exhausting our supply of lies, and ravished by the thought of a shower, we paid FEC and were led to our cavernous room.

What a difference a shower and a change of clothes make. After a wash and a meal, we might as well have been luxury travelers. With high spirits we boarded a horse cart waiting by the hotel gate. First the lake, then a huge pigeon- encrusted statue of Mao passed by us at a trot. Kashgar seemed a mix of Xinjiang adobe and Chinese concrete.

But the Id Kah mosque and the bazaar provided my first glimpse of the Near East.

Above the mosque rose onion towers, topped with crescent moons.

Inside were trees, then a colonnade where men bowed while the muezzin or some accomplice cried "Allah Akbar!" Outside, around the edges of the square, the market stalls began. Music shop damsels sold long-necked, inlaid dulcimers. Spice sellers offered tins full of so many pungent colors they looked like paintboxes. Some inexplicable lumps looked like bones, and proved to be salt. Every other man seemed to sell knives, generally hilted and inlaid with plastic or cheap stones. The rugs--merchants invited us to walk on them, have a nut--were densely piled and as colorful as the spices.

Calling to their elders, children danced around us, as if we were their wares, and they were hawking us.

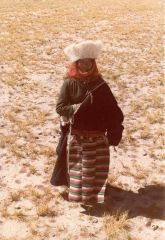

One whole street contained nothing but hat shops. Boxlike embroidered Uighur hats were familiar to us. Stranger looking were the Kirghiz beanies, and oddest of all was a black wool hat shaped like a judge's wig. It would have been easy to clear a courtroom in one, for they stank horribly. Andy was full of export ideas; he particularly liked the rugs, which John confirmed were much cheaper than those in India. For the moment, we three contented ourselves with buying enormous fur hats that were very nearly the size of manhole covers.

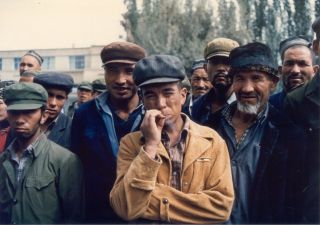

Marco Polo remarked of

Kashgar that the "natives are a wretched, niggardly set of people; they eat and drink in miserable fashion." I felt better

disposed to them. Many actually asked to have

their pictures taken. There is no surer way

to endear oneself to a photographer, especially to one who, until

recently, had had rocks thrown at him by the

aggessively modest. The food, too was good enough. Cooks made noodles by the spectacular method of swinging the

dough like a jump-rope, twisting it, and

swinging it again, until it formed itself into a skein of strands. On one occasion, while I reclined on the airy second

floor of a tea house, the two women cooks

came and asked if I wanted more noodle soup. Then, spying my camera, they smoothed their floury aprons, stood up

straight and held their breath. At the click

of the shutter, they exploded into laughter,

nudged each other, and took my bowl back to the kitchen.

Marco Polo remarked of

Kashgar that the "natives are a wretched, niggardly set of people; they eat and drink in miserable fashion." I felt better

disposed to them. Many actually asked to have

their pictures taken. There is no surer way

to endear oneself to a photographer, especially to one who, until

recently, had had rocks thrown at him by the

aggessively modest. The food, too was good enough. Cooks made noodles by the spectacular method of swinging the

dough like a jump-rope, twisting it, and

swinging it again, until it formed itself into a skein of strands. On one occasion, while I reclined on the airy second

floor of a tea house, the two women cooks

came and asked if I wanted more noodle soup. Then, spying my camera, they smoothed their floury aprons, stood up

straight and held their breath. At the click

of the shutter, they exploded into laughter,

nudged each other, and took my bowl back to the kitchen.

That first night we ate at the new hotel, which served regulation Chinese food. We took a liking to the putaopijiu, `grape beer,' a slightly effervescent winy beverage, preferable to the carcinogenic-tasting beer or the treacly wine. At dinner we made friends with a group of Japanese travelers, who invited us up to their room afterwards. An eccentric Mr. Kikuchi amused us with stories and sketches. His Mongolian features, combined with a local hat, allowed him to pass himself off as an Uighur. He spoke only Japanese, but his sign language was eloquent. He had already secured a dinner invitation from a local family. The rest of us listened, talked, examined his watercolors, shared his dried fish and pickled plums (tastes that remind one of Japan so strongly that they amount to an edible haiku), and drank fierce Chinese spirits.

Somebody spilled some--perhaps to avoid drinking their share--and before anyone else moved, a girl named Eriko leaned forward with her lighter, and the puddle burst into blue flames, then burned away to nothing.

Enjoy Kashgar as we might, sooner or later we had to decide where to go next. We had gone as far West as was possible in China. Rumor held that anyone with a proper visa could cross to Pakistan, but nobody had one.

We could go back the way we had come. But Tibet was not so far away.

In this both Chinese bureaucracy and travelers scuttlebut agreed: of all the places not to enter Tibet from, Kashgar was number one. Deserts, police checkpoints, and the Kunlun mountain range stood in the way. Andy decided it would be wiser to return to Golmud, in company with a red-haired Canadian woman he had met. This time, though, there was no question what John and I would decide.

On our last night in Kashgar we decided to move to the cheaper and more atmospheric (rock gardens, circular doors) hotel located in the former British consulate. Eriko and a Hong Kong girl named Linda had elected to go along with us to Tibet. Linda was very well-traveled and seemed competent, but we worried about Eriko and tried to discourage her.

Though in her mid-thirties, Eriko looked and acted like a particularly silly teenager.

Threats of snow and starvation only made her squeal more excitedly, even as they made us feel hypocritical. So we brought her along. She proved tougher than she looked, which was lucky.

Dusk found us riding a cart in the crowded streets. Our young boy driver had a powerful horse which he liked to race, with maximum shouting, chaos, and risk to the passengers' limbs. Farther away from the bazaar, though, we outran all competition and slowed down. The air grew cool and the sky turned sherbet colors. Infrequent lights gave the street a candlelit air. Restful manure smells drifted by. The presence of growing things seemed more intense when we knew there was desert all around. Eventually we stopped at the hotel gate, paid the driver, and walked through the circular portal leading to our dormitory. A group of friends had dried out some marijuana, which grew by the roadside. It was the first time I had smoked in many years, and I caught a case of the giggles. Shortly they faded away. Staring at the stars we all lounged in the courtyard's dry fountain until quite late.

The next morning I felt awful: it was something I had eaten. The day's bus ride south to Yechung (Karghalik) was, if possible, more painful than the one to Kashgar.

Were we allowed to be in Yechung? Nobody knew for sure, but the shop and inn-keepers suspected something, and charged us double.

Our next destination was Ali (Sichuanhe) in Tibet, and we needed to find drivers who would take us there. At the truck stop we ran into a couple from Hong Kong, Shubo and Shumei (later known as Burt and Rita) who were traveling with an American, Andy, an actor from New York. They had originally intended to skirt the Southern Taklamakan, following the alternate leg of the silk road via Khotan. A recent sandstorm made that route impossible, so we joined forces to canvas the truck drivers for rides.

Nobody was friendly. Some truckers, ignoring our pleas, drove off in the way we wanted to go. Finally, one group allowed that they might take us, but only if we had permits. Immediately we all retired to our rooms, took out our Kashgar permits, and painstakingly added "Ali" to them in Chinese characters. The drivers seemed satisfied with these. I do not suppose they were convinced of the permits' authenticity, but at least they now had insurance that, if caught, we would be punished for forgery, and not they for illegal harboring of aliens. They also charged us 40 yuan each, which did not seem like much.

There were six trucks in all. Linda and I shared the

cab of one of them with a pock-marked,

reptilian-faced driver who seemed to be the leader. Our cargo consisted mainly of cement dust and pieces of metal.

There were six trucks in all. Linda and I shared the

cab of one of them with a pock-marked,

reptilian-faced driver who seemed to be the leader. Our cargo consisted mainly of cement dust and pieces of metal.

On top of it I strapped Linda's and my packs.

Because of mechanical problems, we did not start until mid-afternoon.

In the backs of our minds we realized there was a problem we had overlooked. Where was the police checkpoint? And how could we hide from it, when we were pretending to be legitimate travelers? The problem took on some urgency as we came to the end of town and spotted a whitewashed hut with official-looking red characters on it. Linda pulled her orange hat over her face while I slumped in the seat and, pretending to shield myself from the sun, spread my hand over my face. The driver looked at us curiously.

In a minute we had driven right by. The cops were evidently out to lunch, or dozing in the desert heat.

Now we really were in the desert. There was no vegetation, just bronze light, and dust sifting across the road like powder snow. Later the scenery developed cliffs and hills, on which there was sparse, mediterranean-like vegetation. In the evening we had a flat tire, the first of a daily series. This one came as a terrible explosion; it sounded as if the engine had broken something. Dark fell by the time we could continue, and the driver turned on the headlights. Sending shadows across the landscape, they made it seem more intimate, less of a photograph. Suddenly a luminous flock of sheep jammed the road before us. The driver hit the brakes, waited impatiently for a while, then began shouting, blowing his horn, and flashing his lights. A shepherd appeared, wearing a black wool judge's hat. Once in the road, he jumped in the air, kicked back his legs, and hooted. It was some time before the hundreds of sheep got off the road.

About midnight we finally arrived at a truck stop. A red and white bar

gate was raised at the entrance, and I

wondered if we had not just evaded another checkpoint. We tossed our gear in a dusty room where the beds were all

jammed together and headed for the kitchen.

At this altitude water already cooked somewhat slowly, and in the shadows I saw my first Medusan pressure

cooker, a huge pot whose top screwed down

with a dozen bolts. After a lot of pushing and grumbling, everyone sat down at the rough wooden tables to devour

fried vegetables and steamed buns. There was

no conversation, just slurping and swallowing.

About midnight we finally arrived at a truck stop. A red and white bar

gate was raised at the entrance, and I

wondered if we had not just evaded another checkpoint. We tossed our gear in a dusty room where the beds were all

jammed together and headed for the kitchen.

At this altitude water already cooked somewhat slowly, and in the shadows I saw my first Medusan pressure

cooker, a huge pot whose top screwed down

with a dozen bolts. After a lot of pushing and grumbling, everyone sat down at the rough wooden tables to devour

fried vegetables and steamed buns. There was

no conversation, just slurping and swallowing.

Truckers and passengers alike stared unfocussed at the table or the candle flames.

Early the next morning we came to a wrecked truck that was almost totally stripped. The drivers spent most of the day loading it to be taken back to Kashgar. Meanwhile, we seven lounged on the river rocks.

There was ice in the river, but the sun was warm. I felt it was good to have a chance to get used to the altitude. Marco Polo reported that there were no birds in these high places, but I saw some black, red-billed birds that may have been choughs, as well as some floppy, magpie-like birds.

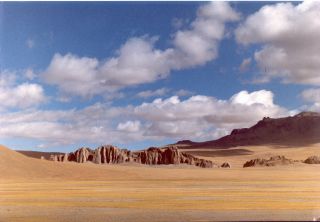

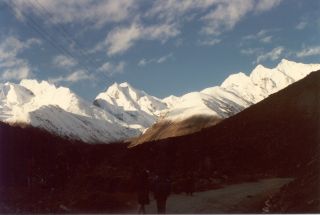

In the late afternoon we started again, moving up among snowy

mountains. They were raw rock, red, green, or

brown. Ramparts jutted from smooth scree slopes. There is a peculiar feeling of elation whenever one reaches a mountain

summit after a long hike. I had that same

feeling now, except that it was continuous. We came to a large river plain at evening.

In the late afternoon we started again, moving up among snowy

mountains. They were raw rock, red, green, or

brown. Ramparts jutted from smooth scree slopes. There is a peculiar feeling of elation whenever one reaches a mountain

summit after a long hike. I had that same

feeling now, except that it was continuous. We came to a large river plain at evening.

Another tire blew, this time a long flapping hiss. The wind was very strong; instant whirlwinds would spring up and disappear in a blink.

At the truck stop we had to wait a long time for food. Finally we got white rice, eggplant and peppers. The cook cut a chicken's throat, then doused it with boiling water. I saw legs wiggling in the pan. We were offered the feet, but declined.

The next day, Monday the 23rd of September, we traveled about 220km along the gravel valley of a peacock-blue river. Our driver pointed out a monument to the dead in the Indian war. This 1962 war, I later learned, was for the Aksai Chin, or stone desert, which we were traveling through. The Chinese won, but I could not imagine anyone desiring this dusty gravel, never mind fighting for it.

There were still soldiers stationed nearby, but they

were quite friendly to us when we stopped

that evening. One young man showed us a decrepit Rubik's Cube and how he worked it. The others seemed bored and

complained that there were no girls.

There were still soldiers stationed nearby, but they

were quite friendly to us when we stopped

that evening. One young man showed us a decrepit Rubik's Cube and how he worked it. The others seemed bored and

complained that there were no girls.

The next day was one we had been anticipating for a long time. We were to cross a very high pass. How high was a matter of contention. One driver insisted it rose 6,980 meters. Only Linda, who had a taste for superlatives, believed this. Our driver's 5,700 meter estimate seemed more reasonable. All the drivers, however, were unanimous that we would surely die of asphyxiation if we had even a trace of a cold. I had a cold, but was more concerned about Eriko, who was turning an inky blue.

On seeing her, the drivers swore ferociously, waved their arms, and took out a few dozen pills which they funneled into the poor girl. There was nothing more we could do, and Eriko wondered if she should write a farewell note to her parents.

A preliminary high pass led into an expansive plateau. I saw standing stationary on the snow-dusted ground: a single goat. Was it frozen or merely contemplating? Later I talked to John, who had been in a truck about half an hour behind me.

"On that pass," I inquired, "did you happen to see--"

"A goat! My god, so you saw it too?"

"That means it was--"

"--frozen!"

"A cast-iron lawn goat!"

"Good thing we're not sleeping outside!"

We had stopped by a green lake to fix another tire.

Around us the desert was thinly studded with

yellow bushes. My gruff driver was beginning to like me, I suspected. During this break he shared his delicious Hami

melon and some bagels with us. Earlier he had

been stopping suspiciously often to relieve himself, always at the most picturesque spots. Nor would he get back into the cab

until I had taken a shot. Perhaps my many

pockets, four lenses, tripod, cable release and other gear distributed about my person appealed to his sense of

humor. The following day he even got out and

stopped two horsemen so I could photograph them.

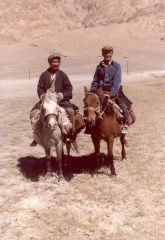

We had stopped by a green lake to fix another tire.

Around us the desert was thinly studded with

yellow bushes. My gruff driver was beginning to like me, I suspected. During this break he shared his delicious Hami

melon and some bagels with us. Earlier he had

been stopping suspiciously often to relieve himself, always at the most picturesque spots. Nor would he get back into the cab

until I had taken a shot. Perhaps my many

pockets, four lenses, tripod, cable release and other gear distributed about my person appealed to his sense of

humor. The following day he even got out and

stopped two horsemen so I could photograph them.

Later that day we stopped at Dead Man's Point for a dinner of goat, eggs, and noodles. On the lake were ducks and seagulls. Then up and up we drove, while the sun set, bronzing the snow, shadowing the ridges, turning the southern sky a jade color. Already, however, the goat we had eaten was bucking in our stomachs. A tailwind drove dust and diesel exhaust back into the cabin. Linda was groaning and I developed a headache shot through with green lightnings. Some time after dark the driver announced that we had reached the highest point. Linda leaned over me and vomited out the window, into Tibet. Our driver lit up a cigar.

The next morning we woke up to the chanting of shepherds. With their dark chests bare to the cold, a group of nomads were affixing packs to each sheep. What was in there? Combs? Food?

There was other evidence besides nomads that we were finally in

Tibet. At the hotel office the previous night

I observed, instead of the usual Chinese sterile affair, a room full of rags, bunting, buddha images, fabrics,

trunks, and a silver-bound yak-butter-churn.

Outside, I saw my first hoopoe, a boldly patterned bird with a large crest.

There was other evidence besides nomads that we were finally in

Tibet. At the hotel office the previous night

I observed, instead of the usual Chinese sterile affair, a room full of rags, bunting, buddha images, fabrics,

trunks, and a silver-bound yak-butter-churn.

Outside, I saw my first hoopoe, a boldly patterned bird with a large crest.

We passed yet more lakes and mountains. Evening fell, and panicked rabbits dashed away from the truck's lights. Finally we arrived in Ali and came into a large truck stop. Everybody felt an impulse to get away, far away from the trucks we had ridden in so long. By the time we all found beds and congregated in a restaurant, we found that Eriko was missing.

Eriko's health had not improved, and we decided that her mind had finally gone. The fact that she had left behind her luggage seemed to confirm our fears. We searched most of the town before we discovered that she had found her own room and gone to bed.

Nobody was feeling too well. John, Andy, and Rita had fevers of some kind. The altitude was still something over 4000 meters. Even turning over in bed was enough to make one breathless. John developed clausterphobic fears, and would startle everyone in the middle of the night by shouting, throwing open the window, and sucking in great draughts of air.

When day came we took Eriko to the Chinese hospital. The staff were very eager to help, and gave us many pills. They refused payment, and when we remarked that their surgical masks would be very useful against the dusty roads, they gave us a stack of those, too.

There were other foreigners in Ali. John had been keeping an eye out for his former college roommate, Steve, who was also traveling in Asia, and who had lived with John in Taiwan for a few months. In Ali, we found him. Since Steve had also picked up friends along the way, there were about fourteen illegal aliens gathered for lunch at a local restaurant.

We told our stories, and they told theirs.

Steve and his friends had feared immediate capture if they took the bus to Yechung. So they hired a truck which later broke down and stranded them for a night, during which the truck disappeared and their food was stolen. An ambulance gave them a ride the rest of the way to Yechung. From there, after nightfall, they crept past the police checkpoint and slept in the desert by the road. Then they caught trucks to Ali.

Other travelers, including a German man with his sixty year old mother, had just lately returned to Ali from a side trip to Kailas, the holy mountain in Southern Tibet, near the source of the Ganges. It was an unforgettable experience, they said, to see pilgrims from three countries, and to yak-pack around the mountain itself.

Unfortunately, these same travelers brought rumors of snow.

We had already heard that the southernmost route through Tibet was closed by snow. Our drivers had also informed us that the Kashgar-Ali road was usually closed by November. But most alarming was the rumor that the road from Lhasa to Kathmandu would close within a month as well. In addition, there was no telling how long it would take to find transportation to Lhasa.

"We've been looking for days now," said Steve. "We've been asking everybody: `Dao Lhasa? Qu dao Lhasa ma?' The whole town must know us. Yesterday a man came up to us and said: `You want to go to Lhasa?'

"`Yeah, for sure!'

"`You come with me.'

"He led us to the public security office! We thought we'd be put in jail or, worse, be sent back to Kashgar. But he never even asked us for permits, just took down our passport numbers and told us not to stop anywhere on the way to Lhasa. Phew. What's more, we think that we have rides for tomorrow."

Back at the truck stop, our group managed to book some

rides as well, this time for closer to $50.

The rest of the time I spent in the nearby bazaar. It was small, but my first crack at the Tibetan market. I bought

some prayer flags--a set of five: white,

blue, green, red, and yellow--and a sash. I was also offered a large sword for $40 and a necklace for $1000! I laughed at

the time, but the jewelry was beautiful: a

symmetric string of two dark beads, then a

large cut red agate, a silver filigree ball, and an oblong brown and

cream cylinder with rectangular spiral

markings as a centerpiece. (A businessman in Lhasa told me, rather to my disbelief, that these geometric stones are

natural and very rare. Those with an odd

number of spiral `eyes', say 7 or 13, can fetch tremendous prices.) I never again saw a necklace to match that

one.

Back at the truck stop, our group managed to book some

rides as well, this time for closer to $50.

The rest of the time I spent in the nearby bazaar. It was small, but my first crack at the Tibetan market. I bought

some prayer flags--a set of five: white,

blue, green, red, and yellow--and a sash. I was also offered a large sword for $40 and a necklace for $1000! I laughed at

the time, but the jewelry was beautiful: a

symmetric string of two dark beads, then a

large cut red agate, a silver filigree ball, and an oblong brown and

cream cylinder with rectangular spiral

markings as a centerpiece. (A businessman in Lhasa told me, rather to my disbelief, that these geometric stones are

natural and very rare. Those with an odd

number of spiral `eyes', say 7 or 13, can fetch tremendous prices.) I never again saw a necklace to match that

one.

I found one other valuable thing in the bazaar. I was trying to take a picture of a big Tibetan with a raffish grin, and a face like an American Indian's. He held up his hand to forbid me, then asked for a picture of the Dalai Lama. I pantomimed that the Dalai Lama was far away in India, and that I could hardly get a picture of him. The Tibetan pantomimed back that I could buy pictures in the next stall for 50cents each. Suspiciously, I bought one and handed it over. My subject clasped the photo to his breast, whooped, made a face and stuck out his tongue for the camera, and then, overcome with hilarity, beamed and grinned like a toothpaste advertisement. I recorded this effect on film, then hurried over to buy the rest of the Dalai Lama pictures.

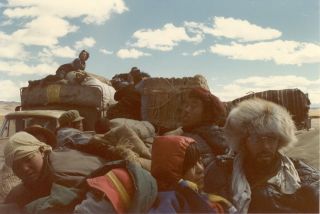

Long before dawn the next morning we found our trucks, only to learn that we must ride in back and that the back was already full of sleeping Tibetans. Eriko and I found a space filled with leaky gas cans, shovels, and boards with nails in them. It did not occur to us to wonder why no one else was sitting there.

We set off, and before

long bumps were sending us two to three feet in the air. We landed, together with assorted sharp objects, on the metal floor

of the truck. My pack ripped and sprouted

holes, while I embraced my camera equipment in my lap. Even the relatively gentle journey across the Kunlun had

broken one of my lenses. Now it felt as

though we were driving on a dry riverbed. It was also very cold. Eriko moaned, screamed and giggled as we shot up and down

like pistons. For a while I distracted myself

by staring at the sky. I counted nine shooting stars before I lost patience and started banging a teapot

against the truck.

We set off, and before

long bumps were sending us two to three feet in the air. We landed, together with assorted sharp objects, on the metal floor

of the truck. My pack ripped and sprouted

holes, while I embraced my camera equipment in my lap. Even the relatively gentle journey across the Kunlun had

broken one of my lenses. Now it felt as

though we were driving on a dry riverbed. It was also very cold. Eriko moaned, screamed and giggled as we shot up and down

like pistons. For a while I distracted myself

by staring at the sky. I counted nine shooting stars before I lost patience and started banging a teapot

against the truck.

No one took any

notice.

No one took any

notice.

We finally paused some time after sunrise, perhaps to eat. I hobbled over to another truck, scaled its side, and saw John couched on bales of sheepskin and resting his feet on bladders stuffed with yak butter.

"Hi guy," he said, "join the party. You're looking a little piqued."

At our next stop, around lunch time, John and I leapt to the ground.

In the middle of our strutting about and Sven Hedin imitations, we suddenly heard:

"Oh my Gawd!"

Turning toward the concrete hut, we saw advancing toward us a beautiful Australian girl (Sorrel Wilby) with strings of turquoise in her hair. She was wearing overalls.

John and I were captivated. The young woman was walking across Tibet, and had permission to do it, too. A professional adventurer, she had bicycled from Chengdu to Lhasa the previous year. Now she was trying to purchase a yak, as her donkey had run away when she was photographing a sunset. She spoke Tibetan, and lived and ate with nomads. To keep sane, as she said, she wrote children's stories about talking wombats. We were the first people of her own culture she had seen in many weeks.

Truck horns and turning wheels interrupted our conversation. Standing on the sacks of yak butter, John and I waved and shouted until we turned a corner. Then we sat and looked at each other, suddenly depressed. We were both wishing we had done the same thing.

Later the trucks stopped for tea, as they were to do every afternoon.

The tea came in bricks, and served by itself it tasted like an infusion of dirt. Generally, though, it was served with yak butter. Blow torches first brought the tea to a boil in battered old kettles. The resulting liquid was poured into a large wooden churn, and a few hairy gobs of yak butter were added. A wooden insert mixed the lot thoroughly. Extra tea, mixed with millet paste, formed an edible sludge called tsampa. Tsampa is inoffensive and bland; the tea is neither. With only a little duplicity I indicated to our hosts that I enjoyed the potent, cheesy brew. Unfortunately I retasted that one cup at intervals during the rest of the day.

The only other available foodstuff was a leg of lamb, which had had a long history. A few passes of a blowtorch cooked the meat a little, whereupon the proprietors pulled off morsels. Hungry as we were to become, we never contemplated eating this.

The day drew on, and we drove and drove. The

scenery was vast and inhuman. There were no

trees, just lakes, snowy mountains, and impossibly clear air. Vista after vista spread out before us.

The day drew on, and we drove and drove. The

scenery was vast and inhuman. There were no

trees, just lakes, snowy mountains, and impossibly clear air. Vista after vista spread out before us.

Occasionally the Tibetans would point at something. With my telephoto lens I could just make out some kind of gazelle in the distance.

Ususally, one or another of our fellow passengers felt in the mood to chant. The high nasal droning suited the wild surroundings. If two sang, they took no notice of each other, and so produced a complicated sort of motet. The others sat and stared into space, or else threatened us with swords when we sat on their feet. Even the Tibetans had colds, and every so often would blow their noses into their hands, then fling the result into the air with a joyous motion.

Sunset colored the entire sky around our bumping, chanting caravan.

Rose and gold decorated even the East toward which we were headed. Later the stars came out again, and the moon shone on the many lakes. We huddled under our sleeping bags, until finally we drew in to a truck stop around midnight. We paid for beds, but the Tibetans just slept on the ground.

Three days passed that way. It snowed lightly several times, almost stopping us once. In the distance we saw nomads, and, once, bubbling hot springs. John's birthday passed and we celebrated it with my last instant food: some very stale salmon rice. That left only a bag of peanut brittle. There was plenty of that, for in Ali I had thought I would never tire of it. My teeth still ache when I think of it.

Finally, on the last day of September, we came to inhabited regions.

There were fields and low houses. On the walls of the houses yak-patties dried, destined to become fuel. Each had a hand print in the center, like the author's signature.

The town dwellers were at their harvest, but would always stop to observe the passing trucks. Our three liveliest passengers, young men with long red or black tassels bound in their hair, would yodel and make Three Stooges gestures at the people in the fields. When I asked, rather foolishly, what meaning those gestures had, I was told they had none at all. When we passed a woman bathing in a stream, though, the gestures' meaning was less in doubt.

The harvesters were no less gregarious. Often we passed them sitting in circles, whereupon they would raise their wooden tea bowls and beckon us to join them. Others, still at their work, would yodel and strike poses with their sickles in the air. They looked like Breughel figures at a disco.

One afternoon we stopped in a fair-sized

town, Saggya, and were told to go amuse

ourselves for three or four hours. This annoyed us, as there was no food

to be had, and apparently nothing to do. I strolled

down one road with my camera, peered about,

and was very surprised to see an English sign saying: Temple Admission 3 Yuan. No Photo.

One afternoon we stopped in a fair-sized

town, Saggya, and were told to go amuse

ourselves for three or four hours. This annoyed us, as there was no food

to be had, and apparently nothing to do. I strolled

down one road with my camera, peered about,

and was very surprised to see an English sign saying: Temple Admission 3 Yuan. No Photo.

I went in, wondering what this desolate land could produce that was worth a dollar to see. The outside wall was newly painted, and the trapezoidal windows had clean black, yellow, red, and white buntings on them.

Inside there was an atrium. I entered a door on the left.

Cylinders of silk brocades hung from the ceilings. Detailed paintings of gods and mandalas colored the walls. In the back, there was a large statue that looked as if it had required a good deal of gold for its formation. On its throne and body were turquoises, corals, and other semiprecious stones.

A Chinese official was pulling at my camera and annoying me. I gave him a very dirty look and he went away. Then I entered the main hall.

A huge gold Buddha flanked by two other statues was the focal point of the room, but a there was a good deal else to observe. Illumination came from a few windows high above the doors, and from innumerable yak butter candles. Off to the left, sitting cross-legged on meter-high prayer cushions, monks chanted euphoniously in thirds. Both boys and old men were singing, the former with the aid of wide, rectangular texts. Before each monk was a brass tea cup; on a table by itself stood a huge copper pot.

Pilgrims would come in, prostrate themselves repeatedly, then move clockwise around the room. I followed them to the left. In shadowy corners, protected by wire, stood still more figures. Below them, in glass cases, were porcelain treasures, gifts from past Chinese dynasties. There were also colored yak-butter sculptures, often framing pictures of the Dalai Lama. Other pictures of that man-god, from old boyhood ones to recent color shots smuggled from India, were scattered everywhere.

I followed the tide around that room four or five times, taking in the buttery-smoky smell, the surge and subsidence of the music, the gleam of gold, the mutters of the worshipers, their dreadlocks, their dirty, pious faces.

"What's all this?" inquired Linda, coming in and blinking in the sudden gloom.

"Kind of a surprise," I replied.

That evening we arrived at Xigaze, the second largest city in Tibet.

As we passed the first buildings, the drivers leant out of the cab and shouted at us to lie flat and pretend we were asleep. We were back where Chinese rules held sway.

We knew when we had come to a hotel when a gaily painted arch passed over us and bright lights and noise rose around us. We all found beds in a gaudy (and relatively expensive at $2) dormitory painted red and pistachio.

Civilisation meant one thing to us: food. On the advice of the innkeeper we went outside and around a corner to where a kerosene lamp glowed dully in a hut. Excitedly we rushed inside and ordered.

"Do you have fish?" I asked.

"We have fish," replied the swarthy, ironic cook.

"Fish, then."

"Do you have eggplant?" asked somebody else.

"We have."

"Great, eggplant then."

So it went round the table. Then we began to wait. It took us very little time to observe that the fire had no chimney. We began breathing through our hats and handkerchiefs. Milk tea helped to pass the time. Finally some of us rushed outside to breathe, and we continued that way a long time, sometimes rushing out to the clear air and stars to be gazed at by children, sometimes rushing back in to sit down, causing the locals in a smoky corner to crane their necks to see what was going on.

It was food that made John and me miss the next day's truck. Fortunately all our gear was in the hotel, and we were in no hurry to get to Lhasa. We were in a hurry to get fed, and nearly ate the cook who first served our long-awaited meal to his friends who came in the back door, and then tried to placate us with cigarettes. Smoke was the thing we hated second most in the world, right after not-eating.

In the end, though, we found enough good Chinese food places to write a small guide to Xigaze cuisine. We turned our attention to the other diversions the town had to offer.

We saw an increasing number of fellow tourists, including even a Smithsonian group in an expensive land rover. I fell into conversation with one old man, and ended up giving him detailed directions on how to climb Mt. Fuji when he stopped off in Tokyo. He would have no trouble with the altitude, I reflected, since just about all of Tibet is higher than Fuji's summit.

Back at the inn, we moved out of the dormitory because of an adolescent monk who, dancing on his bunk in his saffron robes, had listened to his tape recorder songs all night. Our new roommate was a long-haired Japanese man, who impressed us by using Chinese vodka and a can to make a clean, quick stove for instant noodles. He wrote for Brutus, a sort of Japanese Enquirer, and had visited with the rebels in Afghanistan.

"You can get in easy, you know," he informed us in an English accent, "and they ask you if you want to carry a gun. You know, to kill Russians. But you may only answer once. I mean, if you say no at first, that's fine, but they won't give you another chance."

Another neighbor of ours was an Englishman, whose punked-out short hair and robes distinguished him from the usual punked-out young Englishman in robes in that he carried prayer beads, and was actually praying with them. It was he who informed us why the monastery was closed. We had tried to get in but a guard had blocked our way, first with words and then with thrown objects.

"Yeah, the bastard. Wouldn't let me in either. It's these bloody Chinese: the Tibetans don't care. The Panchen Lama is visiting, and the Chinese are keeping everyone out until he goes away."

The Panchen Lama, the second most powerful and holy Tibetan after the Dalai Lama (and more friendly with the Chinese than he), finally did go away, and we were able to see the temple.

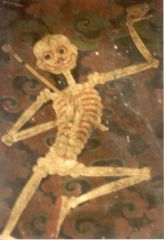

The monastery at Xigaze (Tashilumpo) is a town-sized walled complex of buildings.

Some of these appeared to be neatly-kept private residences. Way in

back, up the hillside, was a large free-standing

wall that looked like a drive-in movie

screen. Temple buildings had gold ornaments and orange tridents on the outside; the inside was like a theme and variation on

the Saggya treasures. There was room after

room of many-armed bronzes (often erotically entwined with female counterparts), yak-butter candles, and colorful

wall painting of gods and mandalas. One such

room was quite a variation indeed: coal-black

walls sported paintings of gory skeltons and monsters; a monster

statue, draped with cloths to hide (I suppose) its

more horrific features, trampled corpses; and

a monk banged drum and cymbals while sour incense filled the room. Reading had informed me that such rooms were meant

to acknowledge the duality of all gods, and

should inspire pity.

Some of these appeared to be neatly-kept private residences. Way in

back, up the hillside, was a large free-standing

wall that looked like a drive-in movie

screen. Temple buildings had gold ornaments and orange tridents on the outside; the inside was like a theme and variation on

the Saggya treasures. There was room after

room of many-armed bronzes (often erotically entwined with female counterparts), yak-butter candles, and colorful

wall painting of gods and mandalas. One such

room was quite a variation indeed: coal-black

walls sported paintings of gory skeltons and monsters; a monster

statue, draped with cloths to hide (I suppose) its

more horrific features, trampled corpses; and

a monk banged drum and cymbals while sour incense filled the room. Reading had informed me that such rooms were meant

to acknowledge the duality of all gods, and

should inspire pity.

To me they meant Hardy Boy adventure and neat stuff.

At the center of all these galleries was a courtyard where monks had gathered, along with some women and children. Many of the monks were sorting prayer flags or hanging them up on a clothesline in the sun. Nearby a dark room was full of wooden printing blocks, lined up on shelves like library stacks. Large detailed flags were on sale here: I bought one about three feet by two feet, depicting a number of buddhas sitting on clouds.

The printing room and the kitchen, which housed gigantic copper vats in medieval gloom, had purposes and meanings that were readily accessible, but I felt the need of someone who could tell me who all the fellows sitting on clouds were. At Gyantse, a fortress town just a short truck ride from Xigaze, I found the tour guide I wanted.

At the end of Gyantse's main street is a monastery with one main hall and an equally large stupa shaped like a wedding cake. There I met a long-haired Italian professor and his wife. He had for several days been waging a courtesy campaign aimed at the monks. This had paid off in free access to the stupa, so John, some curious travellers from Lhasa, and I were given a guided tour. Our professor explained the personalities of the gods in the cubicles that studded each layer of the stupa, as well as such details as what was signified by the position of the hands. He also explained that the drive-in movie screen was a type of fort. Later three avid Japanese and I scaled the one behind the temple, only to find there was nothing inside, just wall and parapet.

Already we were meeting people on excursions from Lhasa, or on their way out to Nepal via Tingri. In fact one such person I met at Gyantse was Anneke, a blonde and raucous Canadian I had met in Chengdu. I was to meet her again in Kathmandu--a pleasing example of what I called variously "Acquaintance Drift" or "Friend Crescendo." That couple you met in Ulan Bator, and remet in Qingdao (where you had those great dumplings) has shown up again in Hong Kong, along with the people you met in Korea, and suddenly an unfamiliar town becomes the stage for a party. Long term travelers, whose home is where they dump their pack, form a sort of community (particularly if they spend a few months in a place they like), that only really ends for someone when he returns to his native country. Even then, a trickle of those still on the move will stop to visit, their notebooks turned to the address you wrote them with a Chinese pen on Indian paper back in a life you wish you were still living.

The bus to Lhasa was a final torment before the promised land. Never have I seen more dust. It rose from between the floor boards. The seats generated it. It worked itself through my handkerchief, and coated my glasses until they were almost opaque. But there was a final lake and a final pass, and then we were in the Lhasa valley.

Lhasa contains both the Potala palace, the mountainous palace where the

Dalai Lama once lived, and one of the most

modern (and expensive at over $100 per room)

Chinese hotels, equipped with every convenience, including oxygen bags in

the rooms. Some suburbs are predominantly Tibetan,

with whitewashed buildings displaying the

usual trapezoidal windows. Other neighborhoods have Chinese apartments. The two hotels where budget travellers stay, the

Banak Shol and the Snowlands, are located in

the Tibetan heart of the city, near the bazaar and the Jokhan.

Lhasa contains both the Potala palace, the mountainous palace where the

Dalai Lama once lived, and one of the most

modern (and expensive at over $100 per room)

Chinese hotels, equipped with every convenience, including oxygen bags in

the rooms. Some suburbs are predominantly Tibetan,

with whitewashed buildings displaying the

usual trapezoidal windows. Other neighborhoods have Chinese apartments. The two hotels where budget travellers stay, the

Banak Shol and the Snowlands, are located in

the Tibetan heart of the city, near the bazaar and the Jokhan.

For ten days I rested in Lhasa. The Potala, the park and lake beyond it, the summer residence, and the Sera monastery were all duly awe-inspiring, but I felt off-duty from the job of ooh-ing and ah-ing at these well-documented wonders. I was more concerned with returning my yoghurt jars for deposit each morning.

Fine, thick yogurt is available in the bazaar, and together with a few pieces of deep-fried flat bread makes an admirable breakfast to eat while one sits in the courtyard of the Snowlands hotel. Other tenants come out to use the pump. One is filling tin washbasins in order to do her laundry. Someone reaches into the stream of water to wet a face cloth. Everyone has learned what priming the pump means. Teeth are being brushed up on the balconies. One uses the boiled water kept in thermoses. Pretty Tibetan girls, clad in dark dresses with colorful aprons, keep the thermoses in generous supply. This morning one such young lady spies a bare-chested bicycler from Montana, spitting used Crest and unwelcome bacteria into a drainpipe. With a graceful upward swing she arcs the remaining contents of a thermos square at him and ducks under the portico. Her peals of laughter precede by an instant his shouted "Hey!" He looks up at the sky, puzzled, and then realizes what must have happened. "That girl," he looks at me, "I swear she has a crush on me." Many of us would like to believe that, but they are just having fun.

We were all having fun. After breakfast I usually took my first turn of the day through the bazaar, which is laid out around the Jokhan.

Knives, beads, jewelry, prayer flags, prayer wheels, boots and clothing lay in stalls or appeared in front of one's nose, offered by an entrepreneurial Tibetan hand. I quickly learned to bargain, not in the dithering, hopeless way I had in other countries, but flamboyantly, Hollywood style. The Tibetans made it easy since they would begin with a completely ridiculous price, say $100 for a bit of embroidery. There is no telling, after all, how rich or stupid a foreigner may be. I therefore would not feel bad in making a ridiculous counter-offer, say five cents. The Tibetan would laugh and roll his eyes. I would grin. He would pat the fabric and lay it out carefully. I would sigh and point at the dirty or worn places. He would shake his head. So it would begin, and I would move on down the street, and incidentally gain virtue by circling the Jokhan.

I met other travellers, new and old friends, in the bazaar, and would compare prices and display purchases. Andy the actor was collecting knives, and soon had a bedroll full of various models, including those he had bought earlier in Kashgar. I remet Andy from Dartmouth, who had flown back from Kashgar to Urumqi and then taken the train to Golmud and truck to Lhasa. John (the Californian) kept company with his roommate Steve, who was still traveling with his loud, blonde stepmother. Often we would all meet at a restaurant off the bazaar, the rock-and-roll noodle place.

The rock-and-roll noodle place had drawn notice because its cassette deck broadcast loud Rolling Stones and Police songs out the door. Inside were mostly clouds of imperfectly aquatic flies, justly excited over the good noodle soup. There were also good momo (stuffed dumplings), and rough tables and benches filled mostly with Tibetans. Tea was served with rock sugar and large whole spices; a lid served to strain them out. The R&R Noodle was a good place to talk to Tibetans, or to friends, or just to listen to music, until the flies drove you out. Some day it will sell T-shirts, I am sure.

After lunch, and perhaps another turn around the bazaar ("Haven't sold that embroidery yet? I'm not surprised. Nobody would pay more than a dollar for it." "Fifty dollars!" "Hah!" "Hah!"), I would return to Snowlands, grab soap and towel from my pack, and go to the bathhouse down the street, which had stall after stall of luxurious steamy showers. Then, clean and sandal-flapping, I would return down the shady street, stopping at a vendor to buy apples, or at the Friendship store which, by some amazing fluke, had a large supply of one-liter bottles of Pepsi. Pepsi and crystallized ginger soothed the sore throat I had had perpetually since arriving in Tibet.

Snowlands was a good place to relax. Some people read (Seven years in Tibet was in great trading demand), others repaired and kept house. I sewed up rents in my pack. The group of bicyclists showed off their equipment and planned their trip to Kathmandu. Eriko celebrated a birthday party with some beer. Everyone traded rumors. We learned that, contrary to what we had heard, the pass to Nepal was open all year, except after storms. We could have gone to Kailas after all! Other stories were unlikley to be believed in the first place: that a Frenchman had been shot in the leg for wandering too close to a missile installation, that Golmud was going to close because it had been hit by bubonic plague. Someone also said:

"You can't go to Kashgar now, you know."

"Oh, yes?" said those who had come from there smugly, "Why not?"

"Well, it seems that at the weekly bazaar--where you can buy everything, you know, including camels and the like--well, some Australians, they say, tried to buy a slave girl, and then, uh, have their way with her. An irate mob stoned them to death, so the Chinese have closed the city until it calms down."

"We love it! Who thinks these things up, anyway?"

The Banak Shol Hotel was a popular place for dinner, because one could pick out stir-fry ingredients in a Sino-Tibetan equivalent of a cafeteria, and because they served yak burgers and potato chips. Yak burgers, or Big Yaks, have novelty value but the lean red meat is too dry and greaseless. It is better used sparingly, as in the yak pizza I had later in Namche Bazar, Nepal. A more usual dinner would be fish, eggplant, peppers, beef and dumplings at one of the numerous Chinese restaurants.

Soon enough dinner conversation turned to how to get to Nepal. By word of mouth we learned where to get Chinese exit visas and Nepalese entry visas, a paper chase that took about two days of walking and waiting. Since we had arrived in Lhasa, we had seen sign-up notices for buses to the border; John and Steve organized one on which most of our crowd would go. It became time to close deals at the bazaar, time to take out cash and wave it: "Last chance! This or nothing." If that was not effective, and it usually was, one could drop the money on the table and begin to walk away with the purchase, slowly. If there were no strenuous objections, you had a deal.

On our last night at Snowlands, Andy the Actor found some Schang, a milky fermented drink, which a group of us enjoyed on the roof. It does not take much to get drunk at high altitudes, so we were not even hung over the next morning, as the bus drew up and we jockeyed for seating positions. After a stop at Banak Shol we were on our way, feeling incongruously as if we were on a field trip, riding as we were a school-bus sized vehicle with no strangers in it except the Chinese driver. Just as we left the relatively fertile valley, we saw two rising and falling dots ahead on the road. They were two pilgrims inchworming toward Lhasa. Our bus rattled past them without drawing their eye.

They had almost made it.

From Lhasa to Xigaze those who had been that way before had the double pleasure of returning to a familiar place and then displaying their superior knowledge to the others. We also felt some of the enjoyment that tour groups must feel: a sense of outnumbering the locals, and an ability to entertain ourselves. At the inn in Gyantse, Andy the actor narrated (at some length) the original Shaggy Dog story. As an encore he almost rendered for us The Moose-Turd Pie Story, one he had mentioned several times before. But he changed his mind again and left us to wonder if the story really existed, or if by continually tantalizing us, he was treating us to yet another Shaggy Dog. Instead he and a Spanish girl put on a display of karate.

Xigaze was the last sure place to provision. We anticipated three more days to the border, with a possible stop at Tingri, the town where most Everest expeditions north of the Himalayas start. At this point the land grew wild and beautiful again. More snow lay on the mountains. We never found Tingri, but stayed at a dirty lodge in the rain.

The next day we kept a watch on the milestones. Word had it that after a certain one began the track to Everest base camp, which five or six of our busload had decided to see. Several of these people, including Steve's stepmother, did not even have sleeping bags or much food, but depended on luck. (They had their share. All made it eventually to Nepal, though Steve's stepmother caught pneumonia and had to be driven out in an expedition jeep, which cost her about a hundred dollars.) We already had one very ill person on board. When the trekkers left the bus, a tall German ran down the steps and fell vomiting on the dust. We offered him medicine when he returned, and then continued on.

During the long ride, through wide valleys and over skinny plank bridges, we had starting singing. We sang every song we knew, which proved to be quite a number, from the Grateful Dead to sea chanties. The driver remained stoic, though sometimes he would gaze at us, then return his eyes to the road. Steve's stepmother had taught us `Old Man River', and we sang it over and over again.

Toward the close of the second day from Xigaze, we started going decidedly up. The road turned to snow, and a cheer went up, followed by a few Christmas carols. This one time the driver set his jaw slightly. The bus slid around some, but nobody was much worried, even when we came to a truck stuck in the road ahead, which had leveled out temporarily. A group of Chinese were standing looking at the truck, and did not display much energy.

Instantly all the able-bodied men on the bus rushed out and latched on to the truck, ready to push. After some rocking and swearing the truck was propelled back on the road. Then we took time off for a snowball fight, until our bus left without us and we had to run to catch it.

It began to snow as we climbed, and we were barely able to see prayer flags and cairns when they passed outside the window. We presumed they marked the highest point of the pass and felt relieved, until we saw some trucks looming ahead of us and came to a full stop. One truck was completely in a ditch.

Our driver turned off the engine, leant back and closed his eyes. When prodded, he just shook his head and opened the door, just in time for a bearded Swiss man to appear and climb in.

"Hello!"

"Hello! Hello!"

"I'm afraid it is not good," he said with obvious relish. "These trucks, they are stuck here for three days. Abandoned. You will have to spend the night, maybe tomorrow also."

Groans from everybody.

"A big storm," he broke in, "--A big storm is passing to the east. We are shoveling now, and must continue before dark. You must shovel too. Come now."

And he went out.

"I don't believe this," said Andy from Dartmouth, who was sharing my seat. "We don't have much food. Some people don't have any, or any gloves or sleeping bags. And now this officious Swiss person--"

"Come on! Come on!" said the officious Swiss person, popping back in.

"You heard him, guys," said Steve. "Let's hit the slopes."

"Women and children first," added John.

Past two abandoned trucks was the Swiss man's van, then another bus, then one last truck, which was blocking the road. We set to work clearing snow from in front of the bus. At first we shoveled away all the snow, but soon we settled for twin ruts for the wheels. At this altitude we could shovel maybe four scoops before gasping uncontrollably for air. So turnover was quick, except when a Sherpa (there were several on that bus) would grab a shovel. They cleared a path as if they were snowblowers. Three or four Sherpas did as much work as the rest of us put together, and with great good humor, too. But the snow fell harder and it grew dark, so after engineering a precarious trail between the stalled truck and the precipice, we retired to our vehicles.

Meanwhile the women, most of whom had declined to leave the bus, had put clothing and tape in the windows and seams to keep out some of the drafts. The driver had a four gallon tin and was melting snow with his blowtorch in the front of the bus. The truck in front of us had a load of frozen cabbages larger than basketballs, and these we snapped or chopped into the pot. Those of us who still had supplies, like cans of meat, added them to the stew, which proved surprisingly good.

Dinner took our minds off, for a while, the fact that we were going to spend a night sitting up on a freezing bus. I was better prepared than most, because I had been planning all along to camp on glaciers in Nepal. However, since my sleeping bag was the warmest on the bus, I felt compelled to give it to the sick German, who did not have one and whose wife was begging for help. It turned out later that he had a dangerous combination of pneumonia and dysentery. But he was not the only one moaning that night--hardly anyone could sleep. I felt most sorry for those who, due to the soup or some other food, had periodically to hurry into the blizzard and experience intimately the temperatures outside.

The next morning it was still snowing, though fortunately not much more had accumulated. There was still about two feet of it to be removed from the road. Early in the morning the Swiss and his driver took off on foot to get help. The rest of us toiled away, refreshed occasionally by some boiled water mixed with a spoonful of jam, courtesy of those back on our bus. Sometime around the middle of the day the sky cleared, and suddenly we had a stupendous view of mountains around us, all white and glossy, like meringue. Down below we could see a plow working its way up the road. By this time, however, we had dug our way to where the snow seemed thinner, and the first driver was ready to have a go. We stood waiting beyond the truck and watched the bus churn through the tracks, tip ominously at the narrowest part (sending snowballs down the steep slope), and then continue past us.

Shortly after that the men in the plow arrived and asked for money. We replied that they could take it out of what they owed us for shoveling. A few people gave in and slipped them some money, but most of us felt that they were just doing their job. China obviously views roads the way the Roman Empire once did, and its maintenance of them in difficult terrain is impressive.

Next we all went back to our bus and took our seats. I watched with interest as we spun our wheels in the snow and lurched into movement. I continued to watch with interest as we reached the narrow section and started to tip, and only panicked when several people emitted the loudest screams I have ever heard. Fortunately we righted ourselves, as the other bus had, and were shortly on our way down.

In a surprisingly short time we had driven down to where the snow stopped, and were again following a dirt road among fields of scree and rock peaks. However, the storm (someone told us later that a hurricane had passed through Bhutan) had not left the road unharmed, and before long the buses were all lined up again. In front of us it looked as if something with a large appetite had bitten away three-quarters of the road.

We got out to examine the landslide, which was very fresh, falling away into the river below. A few feet of level surface remained. We bolstered the side near the river with rocks and dug away at the other to make more road.

When finished, we walked past the slide and took up positions among the brambles (which had turned rusty orange for autumn) on the far side.

The first bus and van crossed without incident. When the passengers remaining on our bus saw that we others planned to remain safely on the ground, they all hurried to join us, even the sick German. Our driver curled his lip at the desertion, slammed the bus into gear, and rolled across. Just after the last wheel passed, the remaining vestige of road slid into the river. Our driver brought the bus to a halt, got out, and with his hands on his hips surveyed the ruin. Then he returned to his seat and stared significantly at each of us as we got back in.

Late in the afternoon we arrived at a relatively large

town--it had two streets--set in a deep bowl

of rocky peaks. We pulled into a parking lot and the driver said we were to spend the night. As we unloaded, the driver

talked to some locals, then came over to tell

us that we would be spending not just the

night, but at least three days there, as the road was completely out

ahead. Then he disappeared, I hope to find a

drink. That was the last we saw of him.

Late in the afternoon we arrived at a relatively large

town--it had two streets--set in a deep bowl

of rocky peaks. We pulled into a parking lot and the driver said we were to spend the night. As we unloaded, the driver

talked to some locals, then came over to tell

us that we would be spending not just the

night, but at least three days there, as the road was completely out

ahead. Then he disappeared, I hope to find a

drink. That was the last we saw of him.

It looked as if the Chinese were grooming this town as a stop for high-priced tourist excursions from Nepal, whose border was only thirty or forty miles away. A new concrete hotel was under construction, and there were a few restaurants, if only the size of shacks. In one of these the two Andys, Shubo and Shumei (Burt and Rita), and I had dinner and decided that we were not going to wait three days to get out of there but would start walking early next morning. For one thing, our visas were going to expire soon, and it would be just like Chinese bureaucrats to send us back to Lhasa to get them renewed.

The town was still in shadow, but the tops of

the peaks were red, when we shouldered our

packs next morning and passed between the boulders blocking the road at the far end of town. It felt wonderful to be walking,

especially walking downhill, at last. The

others felt so too: Andy the actor spun around with his arms out, and Rita laughed. The other Andy and I played

kick-the-stone for a while. Everyone breathed

deeply and watched the scenery, which unfolded more slowly and quietly than it had on the bus. We flushed a group of

snow pigeons, which flew off down the valley.

Later I saw a surprised-looking duck zip past

in the runoff by the road and disappear down a culvert. There was

water everywhere, pouring into the river, shooting

off cliffs. Some waterfalls fell directly on

the road: we could walk behind them.

The town was still in shadow, but the tops of

the peaks were red, when we shouldered our

packs next morning and passed between the boulders blocking the road at the far end of town. It felt wonderful to be walking,

especially walking downhill, at last. The

others felt so too: Andy the actor spun around with his arms out, and Rita laughed. The other Andy and I played

kick-the-stone for a while. Everyone breathed

deeply and watched the scenery, which unfolded more slowly and quietly than it had on the bus. We flushed a group of

snow pigeons, which flew off down the valley.

Later I saw a surprised-looking duck zip past

in the runoff by the road and disappear down a culvert. There was

water everywhere, pouring into the river, shooting

off cliffs. Some waterfalls fell directly on

the road: we could walk behind them.

Others fell such a distance that they turned into mist and rainbows against the black rock, before landing on a forest canopy far below. We began to see trees with such pleasure that we realized how long we had missed them. I finally recognized something familiar that had been nagging me since the previous day, when I had scratched myself on those wet briars by the road. It was a smell--the smell of living things. My sore throat disappeared.

After a few hours we heard trucks approaching, probably those of a road crew. When they passed us, however, we saw John and the others waving at us from inside.

"Those guys!" exclaimed Dartmouth Andy. "Lazy!"

They did not gain any distance on us though. Around the next corner we found the truck stopped before a concrete bridge spanning a gorge. The bridge looked intact, but immediately beyond it was a large mudslide full of boulders. Chinese workmen were crawling over it with dynamite in their pockets.

The five of us barely acknowledged our former companions, but hurried across the bridge and the slide, which was passable. On the far side were some more trucks and a land rover belonging to a group coming from Nepal. Anxious to regain our solitude, we ignored them and moved down the road. Now the trees were all around us; brightly-colored birds flew among them. Mosses and ferns hung from the cliffs. After about an hour the land rover drove past us with the sick German and a few others inside.

Later in a grassy clearing we found a house where four Tibetans, men and women, lived while they worked on the road. They invited us in and gave us some black, salty tea. Then they asked me to take their pictures, which I did, only to find them immediately imploring me for prints. I gestured that there was nothing I could do about it--not that kind of camera--but they thought I was just holding back. Andy stepped in to interrupt, then gave a wonderful mime of the film inside the camera, then wound up, flying to the United States, opened inside a darkroom, developed in trays, and hung up to dry. At the end we all applauded, and the smiling Tibetans turned back to me to continue their entreaties. I then drew a picture of a stamped letter, and indicated that they should write down their address. They were staring at this with great puzzlement when we heard trucks outside and ran out to get a lift.